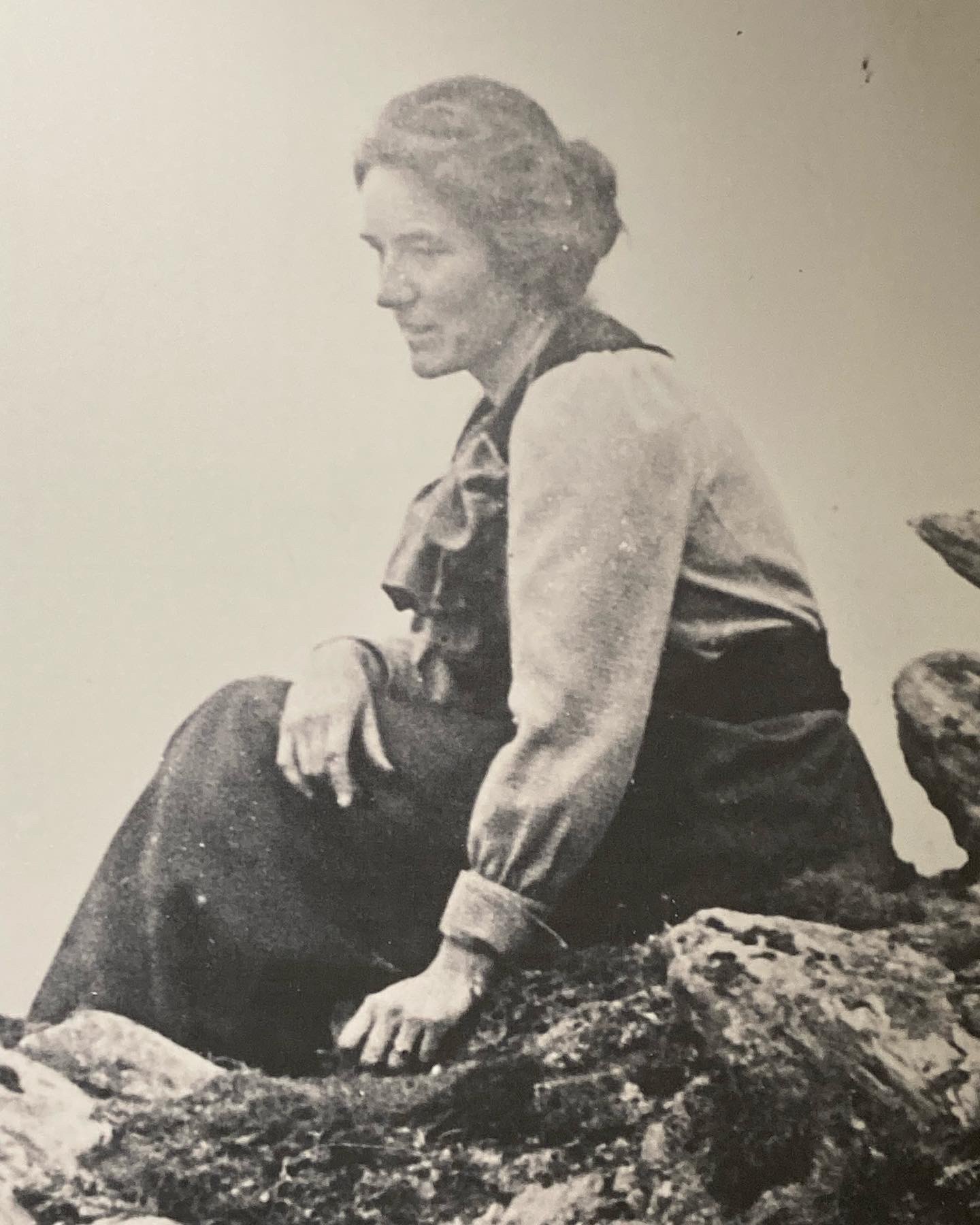

Ethel Mairet

Revisiting my 00’s reissue of Vegetable Dyes by Ethel Mairet, the tone is unsentimental with the unfrilly bracing air of a factual record. Originally published in 1916, to modern eyes it needs a little de-coding; it talks of chemicals which seem scandalous to today’s natural dyer. Chrome. Tin. Whatever Bichromate of Potash is. Things you wouldn’t put in the water course. Things which seem somehow oxymoronic to the whole process of natural dyeing.

Admittedly it’s not a book I reach to for dyeing recipes, but more so the historical framing of natural colour, of what came before. I think most natural dyer’s would see it not as a puritanical manifesto but as a document of it’s time, and a window into the time before that. Ethel is credited for reviving the craft of natural dyeing, picking up the mantle of William Morris, as well as being the foremost hand-weaver of the first half of the 20th century. She died in 1952, but many of her fabrics have a Mid-Century simplicity to them, simple interactions of colour and textures, weft over warp. Haters will say that Ethel was in fact not a very good weaver; being self taught many of her fabrics were plain weave, but often it is true that the best designers operate within the confines of their own skill. It forces creativity in other ways.

In a 1918 essay co-written by her second husband Phillip, she writes of her hope for a new revival of craft, picking ‘up the broken threads of tradition from everywhere’. In her earlier life Ethel had travelled Sri Lanka with her first husband Anada, collecting and recording local craft traditions fading due to imperialism and increasing industrialisation. Harbingers of the same decay England had seen when production moved from cottage industry to factories in the 18th and 19th century. Back in Ditchling, as a craftswoman and educator she ensured the survival of these traditionally female centred crafts, taking on apprentices and weaving students who invigorated the technical aspects of Ethel’s work with their own knowledge.

![Pages from Ethel’s technical notes on British sheep breeds, their characteristics and qualities.]()

Craftswomen and female artists of Ethel’s era are often applauded not in their own right but in their proximity to a more applauded man, in supporting roles, as muses. There is a feyness to this narrative that both mystifies and diminishes their contributions to the wider artistic culture of the day. But not Ethel, whose dye house and weaving studios at Gospels were a serious business enterprise, supporting her extended household.

‘It is not sufficient to be artistic and a good craftswoman: it is necessary to have a good head for business and to follow the trend of what the public wants.’

In 1937 she was the first woman to be appointed Royal Designer for Industry.

Walking around the exhibition last week at Barnstaple Museum, I felt a sense of the woman she was, with a singularity of vision and doggedness. At 48 she established the workshop at Ditchling, where she would live for another 32 years. Learning about her life gave way to thoughts of my own practice, reframing it in my own mind and settling thoughts I often have about the role of craft, who it’s for and why. Ethel’s legacy is as an educator, she believed that the preservation and continuation of traditional craft skills lay in teaching the next generation, to bring them into modernity. In the digital landscape where creativity is often far from the physical act of making, Ethel’s work is more relevant than ever, a reminder of the value of crafts in enriching our material lives.

Craftswomen and female artists of Ethel’s era are often applauded not in their own right but in their proximity to a more applauded man, in supporting roles, as muses. There is a feyness to this narrative that both mystifies and diminishes their contributions to the wider artistic culture of the day. But not Ethel, whose dye house and weaving studios at Gospels were a serious business enterprise, supporting her extended household.

‘It is not sufficient to be artistic and a good craftswoman: it is necessary to have a good head for business and to follow the trend of what the public wants.’

In 1937 she was the first woman to be appointed Royal Designer for Industry.

Walking around the exhibition last week at Barnstaple Museum, I felt a sense of the woman she was, with a singularity of vision and doggedness. At 48 she established the workshop at Ditchling, where she would live for another 32 years. Learning about her life gave way to thoughts of my own practice, reframing it in my own mind and settling thoughts I often have about the role of craft, who it’s for and why. Ethel’s legacy is as an educator, she believed that the preservation and continuation of traditional craft skills lay in teaching the next generation, to bring them into modernity. In the digital landscape where creativity is often far from the physical act of making, Ethel’s work is more relevant than ever, a reminder of the value of crafts in enriching our material lives.